From the "Sacramento Daily Union," 26 August 1871

I've always been interested in discovering how people feel about condors and other vultures. After forty-five years of researching the subject, I've gathered quite a few examples of likes and dislikes. Some examples are serious, even reverent. Others are funny. (Cartoonists love vultures.) Still others are weirdly strange. Some express strong dislike, real revulsion to bald heads and messy feeding habits. Then again, the majesty of the large vultures' soaring flight sometimes brings out the poet in the observer.

I gathered together a lot of those vulture observations in a couple of chapters in "Condor Tales" (Symbios Books, 2004). I'm giving them a curtain call below, with other examples I've stumbled on in recent years.

* * *

In the early 1980s, we were gone from Condor Country, and were living in Gresham, Oregon. I woke one morning before dawn, disturbed by sounds below our bedroom window. When I had managed to rouse myself to get out of bed and look down into the dark yard, I saw strange shapes on our lawn. Closer inspection showed them to be 3-foot high wooden silhouettes of condors, arranged around a banner greeting. Sally had contracted with a local business to give me a life-size “Yard Card.”

When the entrepreneurs came back later to reclaim their artwork (which was rented for a day), they were nice enough to leave one of their birds to add to my collection of vulture memorabilia. It joined refrigerator magnets (“vulture crossing”), signs (an evil-looking condor on a “Welcome” plaque), memo pads (labeled “from the S. O. B.” - sweet old buzzard), pins, tie clips, and an abundance of stuffed animals. (Over the years we’ve found an amazing number of different ones.) My favorite entry, and one of the earliest in my collection, came from a waterfront gift shop in Rockport, Massachusetts. A craftsperson with an imaginative eye had taken black mussel shells, orange crab claws, a little wire, and a jagged piece of driftwood, and had created a perfect model of a group of California condors perched on a rugged cliff. The artist made no claim that they were California condors but, hey, I know condors when I see them.

I guess one shouldn’t be surprised to find the occasional vulture or condor in a gift shop. After all, they have figured in myth, legend, and superstition throughout human history. But their usual persona is hardly the stuff of cuddly toys. They have been most often depicted as harbingers of death, spreaders of disease, Halloween frights, and (ugh!) eaters of dead things - not creatures you’d gladly invite into your home. This evil aspect has proven to be a significant deterrent to vulture protection, prompting some innovative attempts to change the vulture image. For example, my friends in South Africa have used the sexist, but thought-provoking, picture of a pretty girl with an ice cream cone in one hand, sharing it with a Cape Vulture perched on her other arm. Hey, if she’ll do that, can they really be so horrible?

Cartoonists have long found vultures and condors to be great subjects. Hardly a month goes by that I don’t see one in somebody’s comic strip. (Most of them look like a cross between an Andean condor and an African griffon.). Gary Larson’s “Far Side” strips probably have done the most to make condors comically famous. Who can forget the vultures waxing eloquent, while feeding on a huge animal carcass, that these are surely the best of times? Or the condor cheating, using binoculars to spot his meal? Or the condors in the Carrion Cafe, complaining because their meal doesn’t look spoiled? There’s also the “Mother Goose and Grimm” frame of condors gathered at a carcass, with one of them singing “Doe, a deer, a female deer.” And in “Crock,” the two vultures complaining about all the chemicals and pesticides in food: back in the good old days, if something was rotten, you could depend on it. There are greeting card entries, too. I particularly like one by Leigh Rubin, showing a condor reading a book about Einstein and declaring that he’d have given anything to be able to pick that brain.

And here's one from the mid-1970s, about the time we really started to promote the captive breeding program:

California condors have done their share of provoking writers to flights of fancy and bursts of sheer eloquence. Like my other vulture memorabilia, I’ve collected and treasured these bits of Condor-iana. They show the birds from many sides, and run the gamut of their looks, habits, and conservation needs. They are both pro and anti, and both camps have produced some memorable words.

For example, I like P. Flint’s 1940 comment on the condors’ late rising: “...the condor is much like the 1910 Buick when it was first placed on the market. It had to be warmed up before it was able to run.”

C. W. Beebe in 1909 drew on Greek mythology to empathize with the condors and their kin over their scavenging lot in life: “Thus the vultures live Tantalus-like, ever in sight of abundant food and yet unable to satisfy themselves except by the accidental death of some creature.” (To refresh your memories, Tantalus was forced to stand in water that receded when he tried to drink it, and to stand under branches of fruit that he could never reach. Both he and the vultures were “tantalized.”)

Greene and Olsen’s 1941 piece in “Man to Man” Magazine covered all aspects of the condors’ habits and personality: “The condor - nature’s original conscientious objector - will not kill, even to eat.” In the same vein, the condor is “the huge bird who could be a killer but who chooses instead to live in peace with his fellow creatures.”

I like their description of the nestling condor: “a helpless gawk.” And their description of the condors’ plight in the wild can’t help but evoke sympathy for the species: “Today, most of them huddle in a sanctuary... of some eight square miles. This would be equivalent to 35 humans living in a one-room apartment.”(I’m not sure how they did the math, but it creates quite a picture, doesn’t it?)

Even when the stories weren’t memorable, the titles often were. Some of many catchy headings from magazines and newspapers: “Will The Condor Wander Yonder? (One of my favorites.); “Those ‘Forty Dirty Birds;” “Government Flimflam Threatens The Condor (aimed at me, for my supposed collusion with the gypsum miners: see "Flying the Condor By," link above); “Oil And Condors Don’t Mix;” “California Condors, Forever Free?” “California Condors, Forever Extinct?” and “Starving The Condors?”

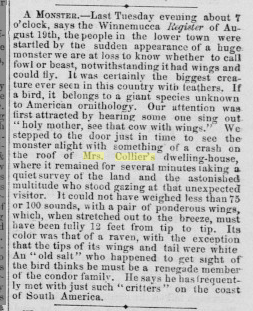

There’s a nice whimsy in an anonymous comment on a newspaper’s editorial page, following one of the October surveys: “A sight you’ll never see: 12 condors counting 115 people.” And maybe more truth than poetry in this revealing note in the "Ojai Valley News" in 1965: “Two condors were sighted in separate instances by valley residents a few days ago. One of the observers, an avid outdoorsman, reports seeing one over Topa Topa bluff. ‘It was flying so low,’ he stated, ‘that if I had had a pistol with me, I could have shot it down’.” And I liked this one from 1931, in which a policeman quickly learned about bird identification.

William L. Finley tried to put an especially good face (well, a good figure, anyway) on the condor: “These mighty creatures that in matchless grace cleave the heavens above our far western mountains and give such a stupendous thrill to the appreciative mind of the person fortunate enough to see them, should never be destroyed.” Carl Koford agreed with him, in part: “The beauty of the California condor lies entirely in the magnificence of its matchless soaring flight.” Then, he spoiled the image: “The California condor in a cage is ugly, pitiful and uninspiring -- just a big black vulture with a naked head and neck.” Granted that this was an anti-zoo statement, not an anti-condor jibe; it still is a memorably unfortunate word picture from one of the condors’ early champions.

* * *

Controversy in the 1950s surrounding oil development and creation of the Sespe Condor Sanctuary was the source of some of the craziest and most impassioned words about condors. A public hearing on the subject in August 1950 - at which most of the participants were pro-oil and anti-condor - produced a number of memorable quotes.

First, from the Opposition:

From Oliver D. Clark, an attorney representing oil interests: “My clients are not less interested in the protection of the wildlife of our country than are the members of the several societies whose representatives have spoken here this morning. I feel, however, that this matter requires as realistic an approach as possible. No one can deny the atmosphere in which we are living, an atmosphere which is fraught with danger to the very security of our existence, and nowhere in the United States is that more true than it is here on the Western Coast, where we are so close to Russia, which is commonly considered to be the main enemy of the American way of life.

“(There is) oil that is absolutely necessary in modern warfare and without which our boys will not have the use of those modern weapons to match the weapons of our adversaries... If it be true, if these birds are to go if we are to have this absolutely indispensable element of modern defense, then we say the birds and not the boys should go.

“I deeply resent the implication that my clients are just oil lease promoters. They are nothing of the sort, they are pioneers, built of that hardy stuff that has made the United States of America the country that it is today, a country able to defend itself against all aggressors and preserve the American way of life.

“So I say to you if this matter is going to be determined in justice, it must be upon the premise of whether it is the bird or the boys who are going to receive your consideration, and I say to you we stand not for the preservation of the bird against the preservation of the boy, if the bird would be destroyed by the development of this area.”

From Frank Morgan, Richfield Oil Company: “I hope General Mac Arthur and his boys in Korea don’t hear about this great battle that is going on here today.”

From George R. Wickham: “The people here today are saying ‘Nuts to you,’ in substance, ‘We want your land’... I have no objection to preserving the condor, I think they are entitled to some preservation, but I think somebody else has got a little right on earth besides the condor. We have got property rights in there. We have had them. Nobody said anything about condors being around when I filed them.”

(The patriotic tone of these comments sounded pretty silly reading them in the 1970s [and hopefully will sound that way again some day], but when compared to our current “war against terrorism,” the sometimes self-serving justifications on the grounds of “national security” have a disturbingly familiar ring.)

Some apparently thought there were bigger issues than our troops dying for lack of oil. From Vic Casner:

“It is very foolish for a few to want to close that country to oil exploration on account of the condor. In fact, by building of roads more people would be able to see them than now and if anything, the condor would be more protected by scaring away the coyotes and the little gray fox which is one of their worst enemies... (there were) 17 of these foxes in the old bunkhouse at one time... so you can see what an enemy they would be to baby condors around their nesting grounds.”

E. S. Huntsman also took the tack that oil development might not be so bad:

“Oil workers or people who are busy are not the type who would be shooting or harming the condors, this is done by hunters and idlers and not by people who are busy.”

And Scott Russell, representing some of the oil interests, was optimistically sure that (like global climate change?) everything would work out okay, no matter what.

“I don’t see any object in this big hue and cry and big noise about the conservation of the condor. If they will just leave them alone, they will take care of themselves. Nature has always been that way, it provides for these things.”

Some people were conflicted and confused. Mrs. Eric Roberts, of the Golden Gate Audubon Society, felt like she might be choosing the wellbeing of birds over the life of her loved ones:

“I can’t help, as a mother, also expressing the views of a mother of an eligible son for military service. I, as a citizen, at the present time feel that my error will be greater in not making an effort to conserve the California Condor and other natural beauties of this country at this particular time that we have the opportunity to make the effort, than it will be if I feel that my boy’s life is in danger from the failure to renew the leases in the area under discussion.”

A man after my own heart - and one of the few who spoke at the hearing that I thought had a feel for the Bigger Picture - was H. L. Shantz. He refused to make it a condor vs. oil issue, instead talking in terms of preserving options:

“Much has been said to indicate that this is a real oil emergency, but, after all, this oil is probably going to be as valuable in fifteen years or fifty years as it is now. It is not so sure that in fifty years we can do anything for the condor.”

Cyril Robinson, long-term champion of the condors while working for the Forest Service, made it much more personal:“I was asked, ‘What is the value of this condor, what is the use of it, what is it all about?’ And, good Lord, ladies and gentlemen, you might just as well ask what the value of the sunset is, or a flock of wild geese in the spring, if any of you have seen that... About all we have got left to fight for in a battle of this kind is sentiment and maybe wits, and we are going to need plenty of that, plenty of it.”

* * *

My favorite quote from the oil vs. condor debates came not from the public hearing, but from a letter to the editor in a Ventura County newspaper. Henrietta Baker combined all the war paranoia, vulture hate, "Not in my backyard" mentality, and general human nuttiness into one long diatribe:

“What latest madness is this? At a time when the imperative needs of our national defense demand the utmost exploitation of our all-too-scarce oil resources, your newspaper is forced to carry a headline ‘Condor Sanctuary Being Barred to Oil and Gas Development.’ The machinery of defense may go without oil, our tanks and planes in Korea may be out of the fight for freedom for want of fuel, the wheels of progress itself may grind to a halt - and for what? - for the protection of a few remaining ‘overgrown buzzards,’ as even your columnist must call them!

“One can understand the restriction of oil development in populated residential areas, such as our beautiful Santa Barbara - but to give up precious oil just to keep inviolate the rocky homes of a few carrion-eating vultures is sheer blindness, or insanity, or both.

“These huge winged beasts of prey are admittedly a menace to young pigs and similar livestock - but it won’t be until some rancher’s young child is attacked that we’ll finally hear the tardy voice of public indignation.

“The bird lovers may be right in their claim that oil development will mean the end of the condors. I say, fine - we’d be better off if they did become extinct - and the sooner the better.”

* * *

As good as Mrs. Baker's criticism is, I think the real champion quotes comes from earlier days. In my opinion, no one turned a phrase (actually, several phrases) against the condors with the flair of H. H. Sheldon. In a 1939 article in “Field and Stream” entitled “What Price Condor?”(and beautifully illustrated with Finley and Bohlman photos), Sheldon’s rapier-sharp words cut to the (funny) bone as he made his case that the condors had outlived whatever usefulness they might once have had. He describes a two month old condor as “fifteen pounds of gawky, ugly chick, dressed in an old mother hubbard of stringy white down, with a bald black face wrinkled like a dehydrated frog. And with a breath which would cloud a photographer’s lens.” The adult is “an evil-appearing bird, dressed in scrofulous black with a bloody head. He looks like a cross between an executioner and an undertaker.” He is “gormand and ghoul, and gorging himself on dead and dying animals is his sole object in life.” Yes, Sheldon admitted, the condor is big, but so what? “Size alone is no guarantee of virtue. If the elephant had the habits of the hyena, no one would want to feed him peanuts.”

My winner on the pro-condor side came in 1923 from well-known California ornithologist, William Leon Dawson. So what if condors eat carrion, asked Dawson: “And who are we that we should sit in Judgment upon a brother who takes his meat a bit rarer than our own? A dead cow is, after all, a dead cow, is it not?”

* * *

I bow out of this treatise with my own special cartoon, presented to me as a going-away present when I left Atlanta in 1969 to head up the condor research program.

Leave a Comment: symbios@condortales.com